Note: Lamestream has been curiously silent on this topic this year. At the 40th anniversary in 2016 there was a special doco made in commemoration that had disappeared from sight when I searched a year or so ago …. I finally located & purchased it after a long trail of emails. I was invited a year ago by one online magazine to write for this commemoration, only to find there was nary a mention of it come the time. Zero. Anywhere. Again I find this curious. A quick search turned up a couple of art exhibitions on topic but nothing. Fifty years on? Such a memorable event? Who controls lamestream? Anyway I happened, quite by chance, to take part in the first leg of this March in 1975, and did write of the experience as invited. I have posted it below FYI … If the event interests you at all that is. Such interest among my peers is pretty minimal I would have to say. Indeed it produces either deafening silence, or indignant reactions. The truth of our histories must be told in order to move forwards. Perhaps in this era with the endless lying we have witnessed, it may provoke more interest? The lying goes way back. It is quite frankly, what woke me up. EWNZ

The Land March of ‘75… I recall clearly that memorable moment, setting off from Te Hāpua in the Far North. Those first steps on the metal road, the crunching of shoes on the stones, eager feet not yet blistered and sore, the excited kōrero going on around us, and that now iconic image of Dame Whina Cooper and her little moko at the front, walking up the hill! And that tag line … ‘not one more acre!’

What an historic moment it was!

I am 74 now. I was only 24 back then. On reflection, it was a year to remember, for reasons I could never have foreseen, and marking the beginning of big changes in my life. I was about to embark on a five decade long learning curve, that like the March, would have many twists and turns. It was a journey that would teach me that no, as the popular belief was back then, NZ did not have the ‘best race relations in the world’. More importantly, I would learn why.

And yet you could say it was only by chance really that I happened to be caught up in the March at all. Perhaps it was providence?

Either way, for various reasons, I’d already dismissed the prospect of going. Being a single parent with my three year old daughter Kahuiarangi in tow, the trip would have posed too many challenges. I was not long out of a violent marriage, so going up there alone was out of the question. I was also very shy. I had already learned a little about the intended March as I’d been following and supporting various protest groups at the time. One of those was CARE, the Citizens Association for Racial Equality. Racism and human rights were a big focus back then. HART, Halt All Racist Tours, was another. That was about South Africa’s official policy of ‘no Blacks allowed’ on their Springbok teams. Consequently, there were fierce protests NZ wide whenever the Springboks toured. There were many folk then who had a real determination to stamp out racism. There were of course the other folk who, like today, believed the aforementioned propaganda on race relations. It was a case of ‘good luck’ to anyone daring to challenge that one.

Those perceptions were challenged however, with the ‘75 March, and then again with the 1981 Springbok tour which saw over 200 demonstrations in 28 centers throughout New Zealand. There were 1500 people charged with offenses related to those events. People were not having a bar of racism, artists and poets included.

So as chance (or providence) would have it then, on 13 September 1975, I received a phone call from my old friend Barnie Pikari. He and his mate Tama Poata had broken down near Marton, not too far from Hunterville where I was living. I’d not seen Barnie for several years. It turned out he and Tama had left Wellington, heading for Te Hāpua in Tama’s Bedford truck, intending to spend time with Tama’s friend Saana Murray in the Far North before the March began. Tama had helped Saana with her book Te Karanga a te Kotuku. I’d been reading it so had learned a bit about Saana’s struggles in retaining her ancestral lands in the north. The truck fix required parts that would take some time to arrive, so he and Barnie had been forced to find other means of traveling north. As it happened, I’d just purchased my very first car, a little 1961 Ford Prefect, so without hesitation I offered to drive them. I’d never driven that far before so fortunately, had given little thought to the logistics of such a long trip. I say fortunately, because had I done so I likely would never have offered! The trip would take more than twelve hours and the roads in 1975 were very different to 2025.

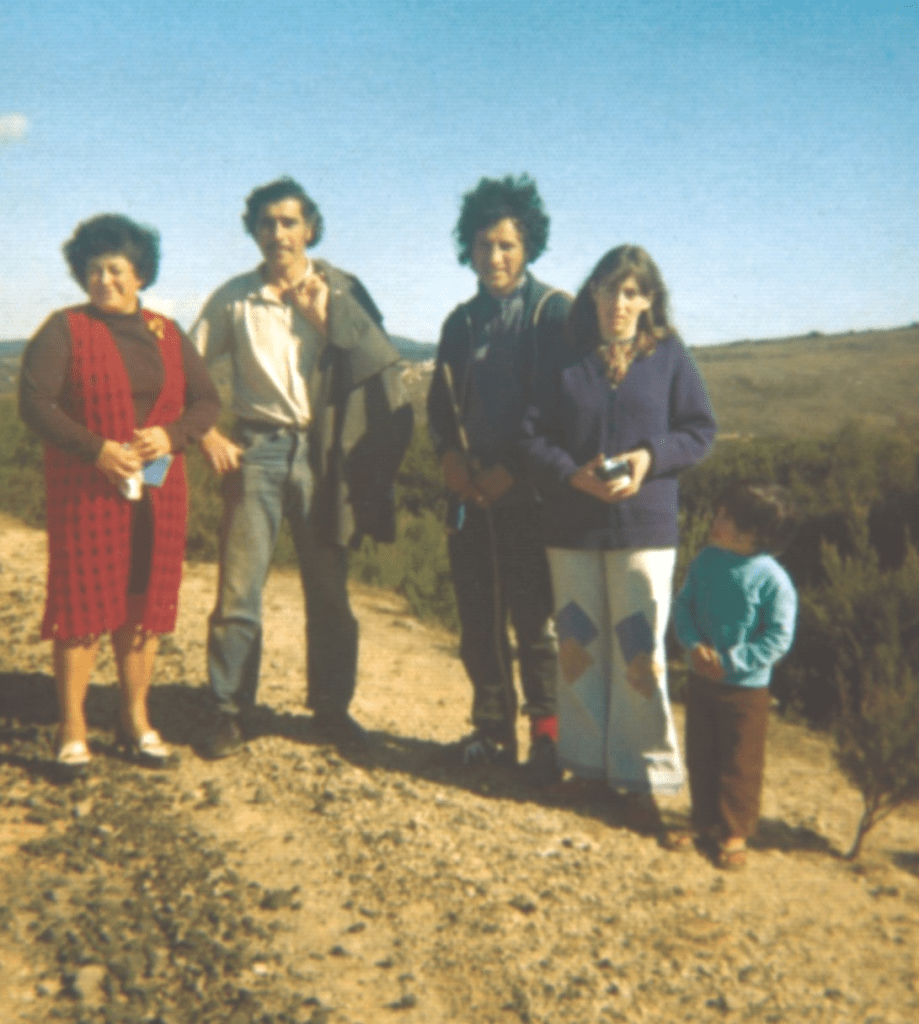

After packing a few essentials we piled into the Prefect and set off almost straight away, taking turns driving. Obviously, we eventually got there, but not without difficulty. Being a first car I’d not thought about things like spare tyres so at Hamilton, when we got a flattie in the middle of the night, with my spare at home in the laundry, we were forced to get very creative and figure out alternatives! Kiwi ingenuity prevailed and Tama and Barnie came up with the brilliant idea of cutting grass from the side of the road and stuffing the tyre. Gradually we limped, regularly re-stuffing it, until we arrived in Auckland and were able to buy a new one. We sped on north then to arrive at Te Hāpua just as breakfast was finishing. We had a short meet up and photos with Rowley Habib and Saana, watched the haka and listened to the departure kōrero, then set off.

I’d decided by then, having traveled that far and having company now, I would stay on and join the March for a while at least, which turned out to be the Te Hāpua to Auckland leg. My daughter, an easy going child, seemed to have coped okay with the trip, and there were other children now for her to play with.

Dame Whina’s little moko was the same age as her so she occasionally came with us in the car. Barnie occasionally drove so I could join the hikoi, sometimes pushing my daughter in her pushchair. Tama had become more involved at an organizational level so aside from the occasional catch up we didn’t see too much of him after that. Along the way we would all stop as a group for refreshments and for tending to sore and blistered feet.

I wish I could say I remember all the content of Dame Whina’s kōrero along the way. In our rush for departure I hadn’t thought of pen and paper, or that I’d even need them, and of course there was no such thing as mobile phones with video and photographic capability. Plus, I had a three year old to care for. Every evening Dame Whina would address those present and explain the purpose of the March, educating us on the historic detail including her own experiences. The concept of government theft of land was pretty new to me, and for most New Zealanders I believe, still is. It blew me away. What particularly struck home from those often fiery nightly kōrero at the respective marae, was our education on the various government Acts, particularly the Public Works Act. Via these Acts, lands were ‘temporarily’ confiscated for other purposes during wartime for instance, then neither returned as promised, nor fully compensated for. Like the lands of the Tainui Awhiro people that had been taken during World War II for an aerodrome, then retained after the war and not returned as promised. Part of those lands had then been turned into the Raglan golf course. It took years of protest and resistance before they were finally returned in 1987. So this taking of lands wasn’t just back in the 1800s as many believe. Folk of my era will know that this kind of information was not imparted to us in our history lessons at school. Rather we learned about the English wars abroad, wars of no great relevance to us. We little knew that we had our own histories of war fought right here … wars of land conquest by the colonial government. Wars over lands that some Māori did not want to sell but which the settler government was determined to have. The richer and more strategically situated lands of the Bay of Plenty, Waikato, Hawke’s Bay, Taranaki and elsewhere, where in all, six million acres were confiscated. In order to justify this, non-sellers were cleverly classed ‘rebels’. Another method of land acquisition has been the perpetual lease system. Māori lands leased for pennies on the dollar so to speak, stripping the owners of their right to manage their own whenua. To get those lands back requires repayment of unmanageable sums to the lessees for improvements made. Mihingarangi Forbes reports on this situation in Tokomaru Bay and the Taranaki and how it has become now an even more unjust situation that no government wants to address. Also mentioned in her documentary, there is the taking of lands from Māori soldiers who went to fight in the world wars. Many returned from war to find they were landless. All with the stroke of a pen. To achieve this land grabbing, there were wars using weaponry, and wars using pen and paper. As the saying goes, the pen is mightier than the sword … in this case yes, those Land Acts did a great job of conquest. Such was Te Kooti Tango Whenua: the Land Taking Court, literally. This was the Native Land Court. For more light on that, one should read Professor David Williams‘ book of that name. He gets very specific about the machinations of that Court, recorded by him as being by far the greater tool for land acquisition than any other. Williams cites IH Kawharu as calling it a ‘veritable engine of destruction’ (ibid p 17). Dr Danny Keenan describes it as ‘predatory’ and ‘ruinous’.

So my learning curve had just begun, not just about land loss, but another important aspect: that of my own whakapapa and identity. I began to research this more after the March was over. My tupuna hail from the Whanganui River. Ko Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi te iwi.

Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au

I am the river and the river is me.

So my dad was Māori but knew nothing of our history or our connections to pass on to us, his generation being well into the assimilation process. Dad’s grandmother was Kiri Te Huatahi. She was raised on the river and her daughter Ani, Dad’s mother, was raised at Pipiriki. Dad’s great grandfather Toi Te Huatahi was from Tāngarākau. Dad’s grandmother Kiri had married a Scotsman, William Ross, and his own mum had married a French Canadian, Albert Vernon. So he and his six siblings were raised in Pākehā ways.

We’d been up the Whanganui River road in search of clues to our history not too long before the March as it happened. I recall him peering across the river from Pipiriki to where he’d been told his Aunt Harriett had been buried when she was just 11 years old. She’d drowned in the river. Her older brother later died as a teen from poisoning by green grapes it was said, according to the Doctor who saw him at the time. We do know now that flour intended for non-sellers on the river was poisoned i with arsenic. I do wonder about my great uncle and whether he somehow fell victim to it.

For my dad, his six siblings and his mum, those were survival years. The way forward for many was seen as learning and adopting Pākehā ways in order to live in a Pākehā world. Language banned in schools, lands largely gone and an assimilation agenda well under way, my dad and his siblings faced as little kids, a very racist world. Folk, they said, would cross the road rather than speak to them in 1920s Whanganui. They were half castes! My Pākehā mum’s widowed mother slapped her face when she learned Mum was going to marry Dad.

Unfortunately the ‘half castes’ end up feeling they don’t belong in either world. Artist Natalie Robertson aptly describes this as standing astride two tectonic plates that shift and moveii.

The racism has not gone away. It’s simply gone underground.

Ironically, and by way of illustration, while on the March we encountered a racist incident in Auckland. It had been raining that night in Auckland and all three of us were very tired. We decided to spend a night in a motel to dry off our wet clothing and rest as I intended returning home with my daughter the next day. The first motel we approached had a sign out indicating vacancies. Barnie suggested I go in and arrange the booking while he stay in the car with my daughter. That was all good. Then when I signaled to him that we had a booking he drove up to the parking area outside. As we organized our gear to go in however, we were told a mistake had been made and there weren’t any vacancies. Being highly suspicious, we promptly drove around the corner and phoned the motel from a phone booth asking were there vacancies. Yes was the reply. They had vacancies, proving our suspicion was correct, that they’d denied us on grounds of race. Being new to such scenarios, I was angered and determined to approach the Race Relations people to make a complaint, however Barnie promptly waved that off as a waste of time.

I’ve concluded from what I’ve witnessed over ensuing years that he was probably right. For most Māori, the scenario described is not an uncommon one.

Returning home, Tama came with me to get his truck, now repaired, to then return and rejoin the hikoi. All updates on the March were from there on by phone and via the nightly news where it was making headlines daily. Tama’s and my kōrero while traveling was further education for me. His long term involvement with human rights, particularly for Māori, made him a deep well of information. The following is information that particularly stood out for me and you will see why.

At the time of the March, I had been a Christian for three years. I’d been converted on a Gisborne marae, at my father in law Hikiera Mihaere’s tangi. My brother in law Truby had explained to me the tenets of the Gospels and my decision there to follow Christ had brought great peace and reassurance to my life. It was very real. Truby was in training in Auckland at the time to be a Baptist minister. With my still new found Christian faith, I was naively confident that God could easily fix racism and restore lost Māori lands, and I told Tama so. His unexpected yet kindly response (recognizing my ignorance) was nevertheless to the point.

It was the Christian Church he said, that had made the largest acquisitions of Māori lands.

This info took the wind right out of my sails. What could I possibly say to that? Three decades on, I would read in The Rich A New Zealand History by Stevan Eldred-Grigg (p 25) that the children and grandchildren of the first Williams generation (missionary Reverend Henry Williams’ family) had become wealthy land owners by the end of that century. Graeme Hunt reports in The Rich List (2000, p22) that at the time of writing some 800 of Henry’s direct descendants owned more land than any other family in NZ. Although later reinstated, Williams had been dismissed from the Church Missionary Society for these extensive land acquisitions. There were some denominations however that forbade them, period. Clearly Reverend Williams did much good in his time of service both to God and to people. I don’t doubt that. Such large purchases of land however, clearly did little good for God’s reputation. And the prices back then were unarguably fire sale. They are purchases that dog the Reverend’s reputation to this day.

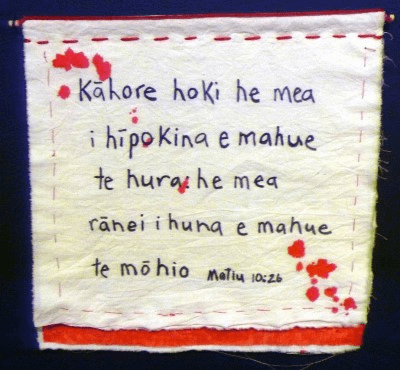

And so, remember that the victors wrote our histories. However, my consolation is that nothing is hidden that won’t eventually be revealed as the Reverend’s good book tells us in Matthew 10:26.

POST SCRIPT

Both Barnie and Tama have passed on now. After the March Barnie joined with Ngā Tamatoa and was part of the occupation of Parliament grounds. He went on to protest vigorously against injustice and racism, both here and in Australia, he wrote articles for the Porirua Community newspaper Te Awa Iti, and co-authored a book, He Whakaaro Ke. He also trained as a Social Worker, and worked for both the Children & Young Persons Service and Māori Mental Health Services. Tama continued his long time involvement in activism against injustice including South African apartheid and the Vietnam War. He wrote a memoir called Seeing Beyond the Horizon that tells his life story, including his impressive achievements in film. He was also involved with initiating the Wai 262 claim, was involved with film, acting in Ngati, a landmark Māori film, plus he acted in and directed many other films. He also promoted indigenous film making in NZ and overseas. At Tama’s passing the late Tariana Turia stated “Tom was one of our quiet revolutionaries who changed our world for the better, in so many different areas” iii. You can find Tama’s book at Steele Roberts’ publishing site. Although now out of print, you will find Barnie’s book from time to time on the second hand book sites.

My dear Dad who weaves intricately into our story, had gone off to World War II at barely 17 years old and had returned amazingly with all of his four brothers. He then met and married our Mum in Whanganui, trained as a builder, then worked hard for the rest of his life, along with my Mum, supporting our family and growing our kai. In his last two years of life, living in the Bay of Plenty with our Mum, he joined the Presbyterian Māori Mission and began learning te reo.

During my child raising years I trained part time as a social worker. After working for six years with Child Youth and Family, I resigned in 1999 and enrolled in a Ucol art class. While studying I attended an art exhibition titled: Parihaka: The Art of Passive Resistance, highlighting a government invasion that didn’t make it into our history books (the victors write our histories). You can read the Parihaka story at their website. I then applied to study Māori Visual Arts at Toioho ki Apiti in Palmerston North. There I would learn more about the Treaty of Waitangi and our true histories, including my own. My art is, among other things, about colonization, the resultant destruction of our environment and about our true histories. I also write. (links below to my websites).

Note: The land grabs continue. The SNAs are another ruse to grab lands.

See here also: Hīkoi of hundreds against Far North SNAs to follow Dame Whina Cooper’s footsteps

Townsville Next Up for Land Grabs?

Catherine Austin Fitts On Helene: “It’s Not A Natural Event” Says It Is A Giant Land Grab

NZ & FURTHER PROPOSED SNA LAND GRABS: 1500 West Coast property owners recently received letters in the mail, out of the blue, stating that their properties have been zoned for takeover by state control …

More on the Aboriginal land grab genocide: 27 elders die within 4 hours of the jab!

i Young, D., Woven by Water, pp 49-50

ii https://www.academia.edu/10943197/A_Journey_of_Belonging_Natalie_Robertson_New_Media_spaces_of_Belonging_in_the_context_of_Maori_art?auto=download

iii Poata, T. Seeing Beyond the Horizon, p 283

Links to my other sites:

Earth’s Blood Stains

Truth Watch NZ

Environmental Health Watch NZ

Just Art NZ

You must be logged in to post a comment.